Recently I have been pressed on two fronts about the ordination of women in the EPC. The first concerns my claim in Women’s Ordination in the EPC: Learning from the CRC that “[Women’s ordination] is not addressed in the Westminster Confession and Catechisms, and so lies outside the system of doctrine taught in the scriptures.” I have been challenged on whether this is an accurate representation of the Confession and Catechisms. The second concerns the absence of the topic in What the EPC Can Learn from the PCA, with some stating that for the EPC to grow numerically and to grow in doctrinal and confessional rigor requires repudiating the ordination of women.

In regards to the first claim, I have several starting presuppositions. First is that the Westminster Divines were familiar with and well-versed in the Reformational documents and debates on both the European continent and colonial America, and that these informed their deliberations and finalized standards. The second is that the Divines, as Puritans and scholastics, did not make theological or liturgical assumptions, but rather developed and defended their assumptions. The third is that the Divines were trying to forge a Puritan/Presbyterian consensus built on the pre-existing English, Scottish, and Irish Reformational confessions and liturgies. The fourth is the acknowledgement that the Assembly published more than the Confession and Catechisms, and so all of the Standards produced were intended to be taken as a unit. Yet, these additional documents were only ever adopted in Scotland, even if they influenced things in Ireland and America. The fifth is that the specific vow and formulation about “the system of doctrine” is not from the Assembly itself, but was developed by the Irish Presbyterian Church in the early 1700s and has been part of the American subscription formula since the founding of the American Presbyterian Church…

Every time I make some variation of the case that the EPC should lean into its Westminsterian, Reformed heritage, I am asked whether in doing so the EPC would lose its ethos. This reaction emerged to my “What the EPC Can Learn from the PCA” post. Usually the PCA’s more rigorous (rigid?) confessionalism is inferred to be part of a contentious dynamic, and that embracing a more confessional posture on the EPC’s part would sacrifice our ethos. In these cases, higher doctrinal standards, greater confessional rigor, and intentionally cultivating a Reformed identity are all assumed to be at odds with the culture of the EPC.

One of the biggest challenges facing the EPC is imagination. We struggle to imagine what a confessionally-grounded approach to ministry and polity would look like. When it comes to the PCA vs. EPC, we struggle to imagine how we could be confessionally rigorous without losing our relaxed ethos. This is a common sentiment, and it’s actually quite revealing — confessionalism is confessing what God teaches in scripture. The Westminster Confessions and Catechisms may get that wrong, but as a church the EPC confesses that we sincerely believe that they get the teachings and system of scripture right. The fear of some is that if we become more confessional then we will lose our ethos. If we have to choose between being faithful to our confession of faith and our “ethos” we should choose faithfulness every time…

There is much my own Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC) can learn from the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). Although the EPC and PCA hold to the same doctrinal standards, the EPC is shrinking while the PCA is growing. The EPC can learn a lot from our larger partner about how to remain faithfully confessional and missionally relevant in post-Christian America.

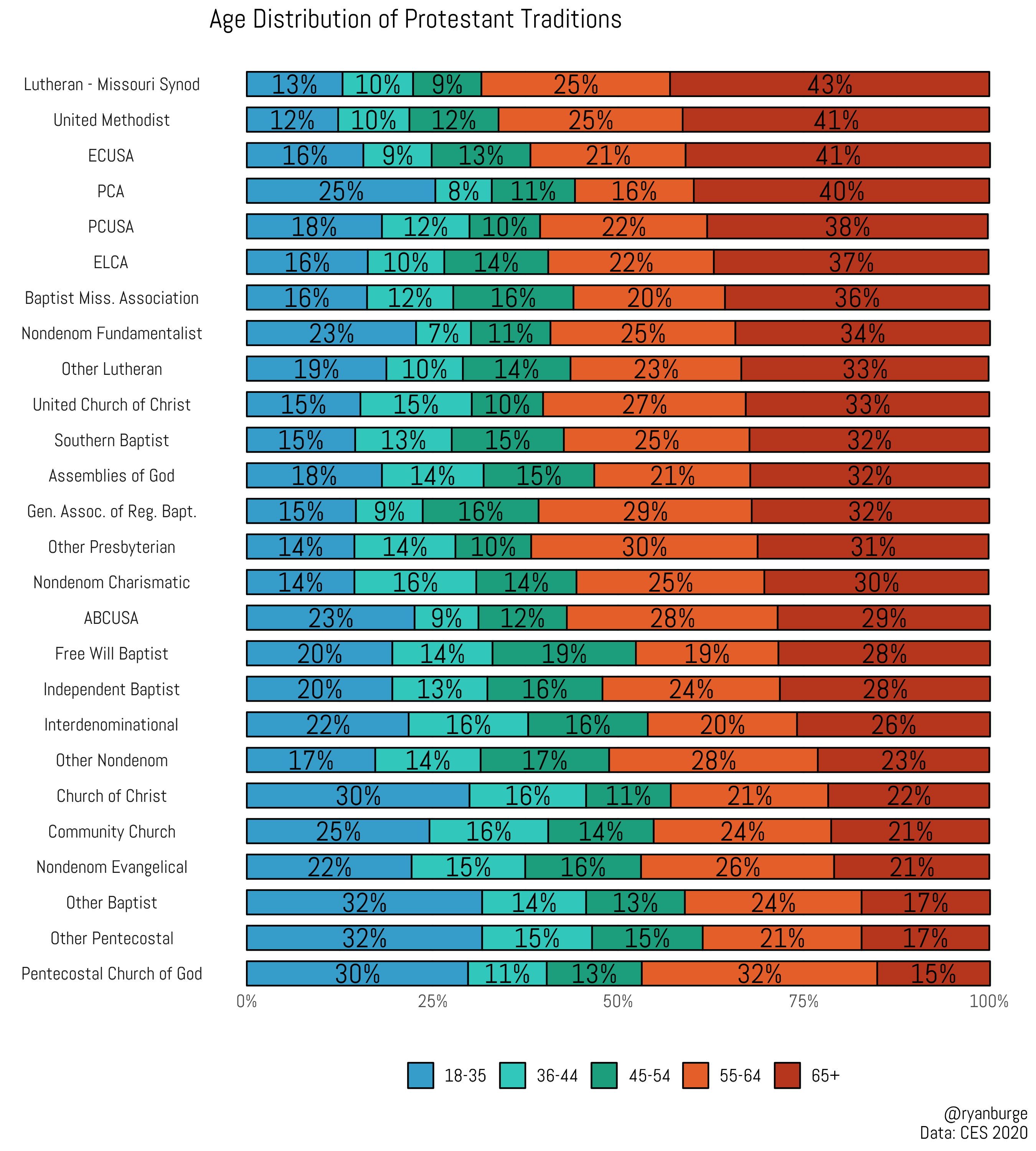

Broadly speaking, the PCA is the only non-Pentecostal denomination still growing in the United States. That should cause every leader in the EPC to pay attention: the only non-Pentecostal denomination still growing in America is a confessionally Reformed, doctrinally rigorous church, and it’s not us.

So, here are the usually caveats at the outset. First, while the EPC should desire for its congregations to grow and to become a bigger denomination, our first goal should be to see Christ’s kingdom grow. Second, numerous individual EPC congregations are growing and healthy and some PCA congregations are shrinking and unhealthy. But on the whole, the EPC is shrinking while the PCA is growing, and I am focused on the general contours of both churches. Third, applying principles of denominational growth to individual congregations is immensely difficult. That requires a culture shift and buy-in. Fourth, most of what makes the PCA successful required steps it took 30-40 years ago. The EPC could try and replicate the PCA’s current practices, but without a similar foundation those practices will flounder. At the same time, the EPC cannot simply duplicate what the PCA was doing from 1984-1994 in 2024; the world is different, and so the application of this foundation will by necessity look different…

I have a new article up on Mere Orthodoxy on how kids stay Christian. Much has been made of the great dechurching and how to evangelize people who left Christianity, but the real scandal is the volume of people who we failed to retain. This article is a summary of how I’ve tried to deal with this in our own church, based scripture and the best sociological data. Here’s the start of the article,

How do our kids stay Christian? Some version of this question has animated both scholarly and pastoral discussion over the last several years, especially as the great dechurching marches on unabated. This is not merely an academic question, but one that has kept younger parents anxious as they watch more and more of their peers turn away from the faith.

Of course, it is the Holy Spirit sovereignly acting as he wills that keeps people abiding in Christ. And of course, God who ordains the salvation of his children has also ordained the regular means of bringing about that salvation, specifically the word, sacraments, and prayer. But how should the church approach those gifts in regards to the discipleship of its children? And what steps can the church take to maintain its children’s faithfulness as they grow into adulthood?

Several recent works have provided invaluable insight into this dilemma, the most important of which is Handing Down the Faith: How Parents Pass Their Religion to the Next Generation (2021) by Amy Adamczyk and Christian Smith. Adamczyk and Smith looked at the religious landscape of North America over the last few decades and came to a simple conclusion: the communities that were most effective at handing down their religion were those that prioritized faith in the family home.

That might not sound earth-shattering, but it corroborated decades of sociological research showing that things like Sunday School, youth group, VBS, Christian camps, confirmation, and youth conferences are either minimally consequential to the maintenance of a child’s faith or in some cases actually counterproductive. Sociologists of religion have known for some time that these programs, while they feel nice, are led by earnest people, and have some anecdotal success stories, are ineffective for passing along the Christian faith…