What the EPC Can Learn from the PCA

There is much my own Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC) can learn from the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). Although the EPC and PCA hold to the same doctrinal standards, the EPC is shrinking while the PCA is growing. The EPC can learn a lot from our larger partner about how to remain faithfully confessional and missionally relevant in post-Christian America.

Broadly speaking, the PCA is the only non-Pentecostal denomination still growing in the United States. That should cause every leader in the EPC to pay attention: the only non-Pentecostal denomination still growing in America is a confessionally Reformed, doctrinally rigorous church, and it’s not us.

So, here are the usually caveats at the outset. First, while the EPC should desire for its congregations to grow and to become a bigger denomination, our first goal should be to see Christ’s kingdom grow. Second, numerous individual EPC congregations are growing and healthy and some PCA congregations are shrinking and unhealthy. But on the whole, the EPC is shrinking while the PCA is growing, and I am focused on the general contours of both churches. Third, applying principles of denominational growth to individual congregations is immensely difficult. That requires a culture shift and buy-in. Fourth, most of what makes the PCA successful required steps it took 30-40 years ago. The EPC could try and replicate the PCA’s current practices, but without a similar foundation those practices will flounder. At the same time, the EPC cannot simply duplicate what the PCA was doing from 1984-1994 in 2024; the world is different, and so the application of this foundation will by necessity look different. Long-term vision and patience are required.

Grasping the Situation

Here is the membership trends of the major (100,000+ member) Presbyterian and Reformed denominations in the United States since 2000. There are weaknesses in this table: each denomination reports membership differently (I tried to include only active, communicant membership); these numbers tend to be generated by congregational self-reporting, which can be specious; and membership does not directly correlate with worship attendance. I selected the specific years to show the collapse of the PCUSA and transfer of congregations into the EPC and ECO, as well as to highlight the pre and post-COVID states. And yes, the RCA’s numbers are accurate; in fact, their 2023 numbers are in and it’s gotten even worse.

| PCUSA | PCA | CRC | EPC | ECO | RCA | |

| 2000 | 2,525,330 | 244,030 | 183,516 | 64,939 | 211,554 | |

| 2005 | 2,316,662 | 261,749 | 186,661 | 73,019 | 197,351 | |

| 2014 | 1,667,767 | 281,790 | 176,683 | 148,795 | 60,000 | 147,191 |

| 2019 | 1,302,043 | 300,119 | 161,280 | 134,040 | 129,765 | 124,853 |

| 2022 | 1,140,665 | 300,413 | 148,933 | 125,870 | 127,000 | 61,160 |

| Change, 2019-2022 | -12.4% | +0.9% | -8.2% | -6.1% | -2.2% | -52.7% |

The PCA is the only Reformed church that has grown since 2000 without relying on transfers from the PCUSA. The PCA even had a number of disaffected groups leave it over the past few years and yet is still growing, including through COVID. The situation is actually worse for the EPC; we peaked at 150,042 members in 2016, and have declined by ~16.2% since then, while the PCA grew by 4.4% over that same period. It continues to worsen when attendance, not membership, is taken into account. The EPC’s average Sunday attendance across the denomination in 2014 was 118,947. It was down to 82,673 in 2022, a drop of a whopping 31.5%. Now, average denominational attendance is harder to measure and report accurately compared to membership, and the post-COVID practice of online “attendance” (which the EPC is trying to measure, but not well) has complicated matters. Yet the reality is clear: the EPC’s worship attendance is declining even faster than its membership. On the other hand, the PCA does not track Sunday worship attendance, but the consensus seems to be that their in-person worship attendance on Sundays is actually higher than their official membership (the OPC is on a similar path of growth and attendance as the PCA, but its total membership of 36,255 is significantly smaller).

This is not how the EPC talks about itself. We tend to talk about how much we’re growing and how the PCA is fracturing. How can the reality be so different? Regarding the PCA, the EPC has confused highly visible debates and a few departures with things going systemically wrong. Reflecting upon ourselves, the number of EPC congregations went from 182 in 2005 to 627 in 2022, but the number of congregations and pastors in the EPC has not yet declined. So the sense of growth we had from transfers in 2005-2014 has continued, even as we’ve shrunk by 25,000 members.

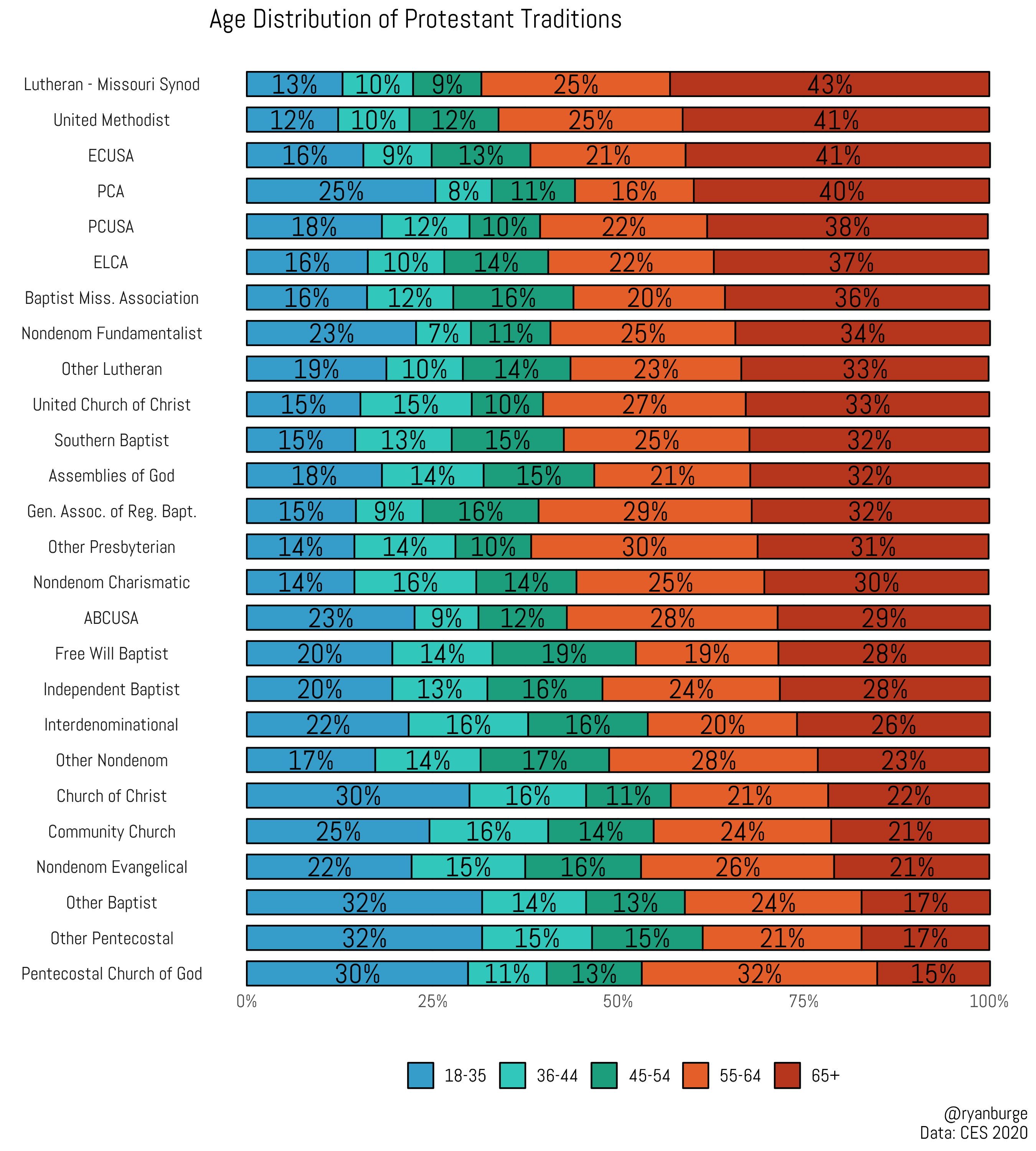

And long-term the situation is equally grim. Ryan Burge is a specialist in religious statistics, and he found that the overwhelming majority of American Protestant denominations have adult populations that are themselves majority over the age of 55 (the percentage of U.S. adults that are 55+ is about 35%), meaning that most Protestant groups are facing a demographic cliff. Pentecostals and congregationalist groups are the only churches with a majority of their adults ages of 18-54. However, the PCA just barely missed that cut, with 49% of its adult membership under the age of 55. The PCA’s 18-35 population is why: This group represents 29.4% of the U.S. adult population and 25% of the PCA’s adult membership, which are roughly comparable. The PCA is the only non-congregationalist denomination in the United States not staring at demographic extinction, and it looks to keep growing in the future.

The EPC is not big enough to make Burge’s data, but we fall into the “Other Presbyterian” category (with the CRC, ECO, and the RCA) where 62% of adult membership is over 55. This is actually worse than the PCUSA (60% of their adult membership is over 55), whose demographic demise is typically treated by the EPC as all but assured. One of the big takeaways just from looking at this data is that the massive influx of PCUSA congregations into the EPC in 2005-2014 masked that the underlying culture and demographics for many of those churches were not primed for long-term health. The EPC is essentially still the church it was in 2005: approximately 75,000 members then and 82,000 worshipers now. And it’s not like the PCA is growing by births alone; it’s averaged 5,000 adult professions of faith and 2,500 adult baptisms a year for the past 5 years. Their church planting and foreign mission ministries are also far more developed than the EPC’s.

To their credit, many of the EPC’s leaders have been trying to take steps to address this (e.g. the Revelation 7:9 initiative, the recent push for every-member evangelism, and the foregrounding of church revitalization and “next generation” ministry training). The PCA is far from perfect and is itself facing a number of challenges (e.g. engaging the working class, catching up to American racial demographic changes), though any issue they have, the EPC has worse. So, in light of the EPC’s real situation of decline and the PCA’s of growth, we should consider what we can imitate for long-term success.

Rigor and Doctrine

Both the EPC and PCA are Reformed and Presbyterian churches that affirm the Westminster Confession and Catechisms as containing the system of doctrine found in the scriptures. One thing that sets our denominations apart is that the PCA is robust about this affirmation while the EPC is minimalistic. We have the “Essentials of Our Faith”, after all. But the PCA’s confessional robustness is the primary factor in their growth. Cultivating a similar confessional rigor while maintaining our cultural ethos should be the first thing the EPC attempts in imitating the PCA.

Yes, doctrinal and confessional minimalism is a possible avenue for church growth. The Pentecostal, congregational, and non-denominational movements are all demographically viable, with non-denominational Christianity now the largest faction of American Protestantism. These groups tend to be doctrinally minimalistic. The problem is that doctrinal minimalism leads to doctrinal and cultural non-distinction: if your church tries to minimize distinctive doctrines and practices it inevitably becomes indistinguishable from broad, non-denominational evangelicalism. But as Reformed Presbyterians, we confess distinctive things. When Reformed churches downplay their Reformed distinctives, their witness, ministry, members, and children all cease being Reformed. Why attend the local EPC congregation that tries to be minimally Reformed when the local non-denominational church is exactly the same without the Presbyterian baggage? Why attend the local EPC congregation that tries to focus only on the evangelical essentials when the PCA church down the road is excited about their Reformed nature instead of minimizing it? The most famous example of this phenomenon is when the Christian Reformed Church burned their wooden shoes in the 1980s. In an attempt to go beyond their traditional, ethnic parochialism and join broader American evangelicalism, the CRC distanced themselves from their historic distinctives, and partially jettisoned their (Dutch) Reformed faith and practice along with their Dutch culture. It led to a massive numerical collapse, and the ongoing conflict in the CRC is about how to either reclaim or reframe the role of historic Reformed doctrines and practices. Reformed confessionalism and Reformed minimalism cannot coexist.

The PCA has taken the opposite tact: they have embraced and led with their Reformed values. No one is surprised about a PCA church not only affirming, but regularly teaching on predestination, unconditional election, limited and penal substitutionary atonement, monergestic salvation, the 10 commandments as God’s moral law, the regulative principle of worship, the spiritual efficacy of the sacraments, covenant theology, repentance unto life, etc. Ministry and discipleship are consciously informed by Reformed doctrinal principles, and the PCA and its congregations enthusiastically proclaim them as scripture’s testimony. And the PCA approaches this through the lens of Westminsterian confessionalism, not a reduced set of fundamental tenets. The PCA is known for its Reformed and Presbyterian distinctives. The EPC is known for letting pastors and churches disregard those distinctives.

The PCA’s ordination standards are very high. Pastoral preparation is theologically and doctrinally rigorous; in the face of growing secularization and post-Christian pressure on the church, the PCA has decided that the only way the church will remain a faithful witness is if these standards are maintained. The PCA’s expectation is that pastors are to possess biblical and theological expertise and that they are trained accordingly. Pastors are to be biblical specialists who can speak scripture to an alienated culture, and this specialization operates from a clearly Reformed and confessional vantage point. It is through this pastoral approach that the PCA’s theological culture and health is maintained.

There are many ways to assess congregational health, but the PCA first evaluates church health on confessional terms. Is the biblical gospel being preached, the sacraments being properly administered, worship being performed purely, discipline being enacted? These questions are frontloaded and never taken for granted. Other questions about evangelism, being a sticky church, mercy ministries, skill of musicians, neighborhood demographics, budgets, valorizing the past, etc., are secondary. Those are important topics, but don’t supersede (by either commission or omission) the bigger doctrinal categories; the same cannot be said for the EPC at this moment.

The missional fruit for the PCA is clear: by being center-bounded on a robust confessional system for their pastors and churches, the PCA has successfully adapted to our culture and built healthy congregations without losing their Reformed distinctives. It may seem odd from an EPC perspective, but the PCA’s stricter approach to Reformed theology has granted them greater flexibility; having a broader foundation and knowing their center clarifies their missional parameters. In the EPC’s case, doctrinal minimalism leaves a void that gets filled with other cultural values, which becomes a lot more difficult to work around (e.g. downplaying the regulative principle more easily leads a congregation to elevate a particular worship style, which then becomes central to their identity, making it much more difficult for them to adapt).

So how does the EPC get there? Since we share the same doctrine as the PCA, in some ways this should be easy. But on the other hand, we already share the same doctrine as the PCA and the reason we don’t want their kind of rigor is because we have historically prided ourselves on being more relaxed. Changing that desire requires a massive cultural shift. That’s only going to happen if the ecosystem of the EPC changes, which must be driven by the same thing driving the PCA’s culture — their pastors. No amount of resourcing, publications, initiatives and strategies, denominational hires, or conferences can shape the culture of a church like its pastors. And that pivot requires intentionality and time, which demands patience. This is a change that will occur on a timeline of decades, not a few years.

So the first step is pastoral preparation. This is a drum that I’ve been beating for awhile, but in summary we should a) prioritize our candidates going to and being recruited from confessional Reformed seminaries that require the biblical languages; b) invest significant money in making sure that happens; c) institute practical experience requirements for pastoral candidates; d) have ordination exams that privilege systematic and biblical theology, and where the bar on Reformed confessional knowledge and reasoning is raised. All of these things characterize the PCA’s approach and are crucial steps that the EPC can take in forming and selecting its pastors.

The second step is to intentionally change our vocabulary at GA and presbytery, particularly from the stage. The EPC’s leaders can set the tone of the denomination, not only in how they speak about things but also in who and what they put before the different courts of the church. Organizations gain what they celebrate, and we should be pushing an explicit Westminsterian way of thinking and doing things. When the EPC is self-described by our leaders we should stop contrasting ourselves with our Reformed sister denominations by privileging our essential/non-essential ethos. Instead, we should celebrate our Reformed and distinctly Westminsterian way of reading scripture and doing ministry. As B.B. Warfield put it, Reformed theology is “Christianity come into its own”, and the EPC should happily and clearly communicate that along confessional lines. There are important things that distinguish the EPC from the PCA, but our doctrine is not one. If we are going to contrast ourselves with other Christians, we should do so by emphasizing our confessional system over and against broad evangelicalism. The EPC is no minimalistic collection of congregations, but possess a rich doctrinal treasury that will pay off in post-Christian America. This change in language and emphasis from the stage will help shift our culture, and signal what our denominational expectations and values are, particularly for Ruling Elders who drive pastoral search committees.

Decentralized Polity

The PCA’s polity is Presbyterian and decentralized, which is a boon for their growth. The organizational structure of the PCA is bottom-up, meaning that the direction, energy, and action for ministry is primarily local and regional. The PCA’s culture prizes pastoral and congregational ministry as the prime locus for gospel ministry and their structure reflects this. The administration and organization of the denomination is designed to maximize the flexibility of lower courts of the church; the presbyteries of the PCA do not to wait on permission from the denominational administration in order to act. The reduction of bottlenecks means that the PCA is more much missionally agile and culturally responsive than more centralized Reformed denominations, like the PCUSA and CRC.

This is also means that ministry strategy is driven by regional (i.e. presbytery) interests, rather than national priorities. And this makes sense: if local pastors are trusted as specialists and leaders, and local congregations are the drivers of gospel ministry, then this should result in regional collaborations that are driven by local ministry, not national directives. Presbyteries are the incubators of regional, and therefore, denominational missional priorities. Campus ministries and church planting are the obvious examples here — the PCA’s church planting success has been borne out of local churches banding together in their presbyteries for this cause.

The PCA does have significant administrative infrastructure, but it flowed out of this culture; it did not create it. The PCA’s church planting and campus ministries are responsive to and presume a locally and presbyterially led church, and coordinate as partners rather than directors.

There is no equivalent in the PCA of the EPC’s National Leadership Team that “seeks the mind of Christ for our denomination” and can state what “God is calling the EPC to be” or can develop “vision and strategies that express what God is calling the EPC to do” or is ever described as being akin to the Session of the General Assembly. Nor do their presbyteries have executive councils that oversee the work of presbyteries and their churches or are ever described as akin to the Session of the presbytery. The EPC’s arrangement encourages a top-down, one-size fits all culture: the national leaders and administration set the direction for the church, and the regional subsets implement these strategic priorities as they defer to the top for direction. The PCA, by simultaneously having a stricter doctrinal standard and a “looser” polity, has freed their congregations and presbyteries to be entrepreneurial and confessional, and their growth is the fruit of that.

One of the symptoms of this is the lively debates that happen in the PCA. Many in the EPC look aghast at the arguments that happen, and sometimes the PCA does have a contentious streak. However, these debates are a sign of health. A denomination of 390,000 is going to have a larger variety of perspectives than a denomination of 125,000, and the PCA takes doctrine (i.e. God and his word) seriously enough to heartily discuss those perspectives and their effect on the church. And since the PCA treats its pastors as specialists and presbyteries as the drivers of missional priorities, then the staff and leadership of the PCA cannot control or set the terms of the denomination’s debates. There is no 15-minute debate limit for issues in the PCA GA, and since their pastors are treated as capable experts, issues are thoroughly examined, not only for doctrine but for their missional implications. Likewise, presbyteries do not exist to ratify what a GA has recommended, but are themselves deliberative bodies, exactly as you would expect to be the case in a bottom-up denomination. The pastors and presbyteries of the PCA have a direct say in the vision and strategies of the denomination, and those priorities arise from the grassroots of the denomination, not from the top. And the proof is in the pudding: this process has led to a doctrinally sharp and missionally effective church that sets the pace for the rest of the North American Reformed world.

How does the EPC get to a more decentralized, entrepreneurial state? First, we need smaller presbyteries. Presbyteries are strongest when they are able to foster local partnerships. The rounded average of churches per presbytery/classis in the following denominations is: PCUSA (52); EPC (39); PCA (22); CRC (20); OPC (17). The EPC needs to increase the number of its presbyteries by around 50% to have a ratio close to the PCA’s, and that should be a goal. This allows for greater proximity and familiarity to foster pastoral and congregational collaboration. Multiplying presbyteries also allows the newly formed groups to reexamine their inherited practices and break out of dated routines and structures.

Second, the EPC’s presbyteries need to own being bodies that deliberate rather than ratify. Something that often happens in the EPC is that our presbyteries vote to approve something because it sounds nice or we want to be pleasant, not because any of our churches are actually planning on following through. This leads to constant missional whiplash. Regional collaborations should be driven by friendship and partnership arising from within the presbytery’s pastors and churches, not by fiat. Efforts towards church revitalization and church planting are good examples of this. These, including the terms on which they are done, should be set by presbyteries. Trying to bootstrap ourselves to the PCA’s level (e.g. presbytery church planting coordinators) without the requisite developed network of bought-in churches will fail. This takes time, even decades. The potential cost otherwise is a lot of failed churches, disillusioned congregants, burnt out church planters and pastors, and wasted money.

Finally, we should amend our Rules of Assembly to try and encourage a decentralized polity. Adjusting things so that presbyteries have more ownership (e.g. ordination exams; defining church health parameters) will reduce bottle necks and increase regional ownership. Requiring amendments to the EPC’s constitution to first originate as overtures from a lower court before they are considered by GA would encourage our presbyteries to become centers of deliberation and leadership. Returning the National Leadership Team to something like our old administrative committee would help reset the EPC to a grassroots posture and encourage presbyteries to take greater ownership of the church’s mission. Requiring things like denominational officers and their job descriptions (e.g. Assistant Stated Clerk, Chief Parliamentarian, World Outreach Director) or denominational agencies, their heads, and strategic plans (e.g. Church Health, Church Planting) be put to a vote at General Assembly, or perhaps even ratified by the presbyteries, would help reestablish a bottom-up, bought-in direction in church polity. This shouldn’t seem radical to the EPC, not only because this is normal in other Reformed churches, but because we already do this for Stated Clerk, the Chaplain Endorser, World Outreach’s 5-year master plan, and the EPC’s position papers. Amending the Rules to allow for longer floor debate opens up the possibility that our General Assembly will meaningfully deliberate on important topics, which increases buy-in and encourages a culture of pastoral expertise and initiative.

Catechize Children

The PCA has been spectacularly successful in retaining children who grow up in their church. A few years ago I stumbled upon some data that, infuriatingly, I cannot find again. It showed that the PCA, OPC, and Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (WELS) were the most effective denominations at retaining their children into adulthood. The reason was simple: they thoroughly catechized their children in the doctrines of their church. The PCA’s demographic numbers bear this out — they are great at inculcating the Reformed Christian faith in their kids. PCA kids know PCA doctrine, which is robust and able to provide stability in our post-Christian, secular world. For the growth of the church this a non-negotiable. As Rodney Stark showed in his classic The Rise of Christianity, the growth of Christianity has always been tied to how we raise our kids in the faith. Any growth strategy that doesn’t lead with this is doomed to failure.

This is something that should be easy for the EPC to implement. Our churches should not be satisfied with a generic, evangelical discipleship program for our children, but should prioritize a rigorous curriculum of biblical content and Westminsterian doctrine. How our kids stay Christian is important, and the EPC should stress a distinctly Reformed approach in our passing along the faith.

The EPC should embrace founding church-based schools to accomplish this. The CRC and Lutherans, including WELS, have done this well. The Reformed Episcopal Church (a subjurisdiction of the Anglican Church of North America) has called on all of their parishes to make starting a church-based school their number one missional priority. This could be an extraordinarily effective route in building the kids of the EPC up in their faith amidst our post-Christian age, as well as serve as entry point into the church for people in the community. This would be a good way for nearby EPC congregations to partner, and is the sort of low-hanging fruit that a denominational agency or staff would be well-positioned to assist in coordinating and resourcing. Perhaps the EPC should call upon every congregation to be a Parent, Partner, or Patron for a church-school. Once again, the numerical pay-off for this is in decades, not 2-3 years. But generational investment that works leads to an institution that endures for generations.

College Ministry

Perhaps the PCA’s best initiative is Reformed University Fellowship (RUF), their college campus ministry. This ministry is one of the best explanations for the PCA’s growth, resiliency in the face of secularism, and its strong young adult demographics. There are a few things that distinguish RUF and its success in helping the PCA grow. First, RUF, like the rest of the PCA, is unabashedly Reformed in its doctrine and practice. College students in particular, especially in our secular age, long for substantial faith that provides good answers and is intellectually satisfying. Second, on top of the RUF vetting process, RUFs and their campus evangelists are pastors screened by and accountable to PCA presbyteries. RUF is successful because it has buy-in from local congregations and the regional church. Third, RUF is very intentionally a servant of the local church, never an alternative, always directing students to the church. And since RUF is Presbyterian, it operates from a base of local church support and investment. Which means that, fourth, RUF is not only Reformed, but as a ministry is coded specifically for the PCA. In short, RUF is always Reformed, is owned by the local and regional church, and PCA churches direct their college students to RUF, which directs graduates back to local PCA congregations. When RUF students graduate, they look for PCA congregations.

The EPC partners with the Coalition for Christian Outreach (CCO), which is a wonderful ministry and a beneficial partnership. But there are some drawbacks to this partnership which will prevent CCO from having a similar effect on the EPC as RUF has on the PCA, at least without significant adjustment. CCO’s model is to partner with local churches, so that the congregation provides the campus minister and funding (or the staffer fundraisers) while CCO provides vetting, resources, and oversight. The benefit is that local churches don’t need to worry about training and administrative structure and the campus ministry is owned by the local church. The drawbacks are that if CCO has already partnered with a church of a different denomination (say, Methodists) on campus, the interested EPC church has limited options. Sometimes local churches of different, compatible denominations partner to support a CCO ministry (e.g. CCO at the University of Pittsburgh is partnered with ACNA and EPC congregations), but otherwise an interested EPC church may just not have any partner options if they want a Reformed campus ministry. If an EPC highschooler goes to college and begins attending CCO, there is no guarantee that it is EPC affiliated or even Reformed. While the CCO campus minister works for the local church, even if they are EPC they are not required to be vetted by a local presbytery, and will be duly influenced by CCO’s institutional values and framework. That’s just the reality of institutional influence, and CCO is broadly evangelical in nature, not Reformed. Students who attend RUF’s big Summer Conference attend a Reformed, PCA gathering. Students who attend CCO’s annual Jubilee Conference attend a broadly evangelical gathering, and that cultural interchange will influence the campus local ministry. CCO is also not EPC coded — it is CCO coded, and at best, branded as the ministry of the sponsoring EPC congregation. There is no CCO/EPC equivalent to the music of Indelible Grace, which moves seamlessly through RUF to Summer Conference to PCA churches. CCO is not a pipeline to EPC churches post-graduation the way that RUF is for the PCA.

That’s not inherently a bad thing, since the EPC’s main goal should be kingdom growth, not EPC growth. It’s also not clear to me how effective attempting to replicate the PCA’s strategy will work without serious adjustment; RUF grew rapidly in the 1990s and there are a finite number of colleges and a finite number of college students interested in Reformed Christianity on those college campuses. That being said, the EPC should make college ministry a top priority and take the long view. Campus ministries are primed for local church initiative (CCO’s lead story on church partnerships is about First Presbyterian Orlando, an EPC congregation) and regional church support. Presbyteries should consider pooling resources to assist EPC congregations adjacent to college campuses start a ministry there. If CCO is already present with a non-Reformed church, then a campus ministry exclusively associated with the local EPC congregation or presbytery might be necessary. If RUF is already there, then perhaps the campus doesn’t need a second (or third, if the CRC’s creatively named “Campus Ministry” is also present) Reformed campus ministry. Or maybe the campus could use two Reformed campus ministries, both CCO/EPC and RUF, which together demonstrate a unity in mission on campus just like there is a unity in mission between the EPC and PCA. If CCO’s administrative structure allows for it, an EPC sponsored chapter should consider doing cooperative work and attending conferences alongside RUF and other expressly Reformed ministries rather than the generically evangelical.

Any stronger push for EPC campus ministries should treat campus ministers as pastors ordained by and accountable to the presbytery, like in the PCA. This creates presbytery vetting, accountability, and buy-in, even if the ministry is fully funded by the local EPC congregation. It also helps ensure that the Reformed emphasis remains constant in the campus ministry and helps keep the CCO ministry not only coded for the local church, but for the EPC.

Cameron – this is wonderful, and I am grateful for both the descriptive and prescriptive elements of what it is that you’ve proposed here. A hearty “Amen” from me in response to all of this, and I feel a deep sense of affinity for your proposals here. A couple of thoughts here which are not disagreements but more of ways of advancing a discussion about these very helpful thoughts:

1) Regarding “Rigor and Doctrine” – what the EPC would benefit from is the nurturing of a distinctive theological culture as much as we need to retrieve our theological heritage as Reformed Westminster Christians. There is a very real reversion to the lowest common denominator of the Essentials within the EPC, and Westminster can be almost sheepishly subscribed to. But while the PCA is much more full-throated in its commitment to the Standards I also think that it is not all clear within the denomination about how to inhabit those commitments. The difference between the Keller wing and the TR wing of the PCA is not insignificant. Just as important as re-committing ourselves to our confession is also how we the Standards are a theological framework for ministry (see WLC 167, for instance!).

Also, this is quite anecdotal but it seems to me that those who are more recently seminary-trained are much more likely to have Confessional instincts when it comes to serving in the EPC.

2) I learned a lot from your thoughts about de-centralizing our polity. It seems to me to be a call to re-commit ourselves to the work of tending to our institution rather than simply using it when it is convenient (i.e., a place to stand where we don’t have to have certain conversations). But I wonder what room you would make also for the “movement” aspect of our life together? I’m thinking about Keller’s dialectic between the institution (presbyteries do a good job of calling one another to account and identifying departures from our core commitments) and the movement (missional impulses that can exist across presbyteries which call us toward something differentt). It seems to me that GA is designed more for the latter than the former these days. For what it’s worth, I see a lot of various movements across the PCA – from the Aquila Report to Beautiful Orthodoxy to Gospel Reformation Network to you name it.

Again, thanks for this. I love the conversation you’re having here.

Hi Joey,

I agree with you on both counts. The movement in the PCA associated with Tim Keller presupposes most of what I put here. Keller himself would say that his confessional theology, inspired by the Neo Calvinists and Puritans, was the substructure of his missional theology. In fact, though I’m probably more associated with the “TR wing” of the EPC (if there is such a thing), I’ve been really inspired by Tim Keller’s 2022 call for thinking through revitalizing the American church. The PCA has a lot of diversity, but what has made that diversity possibility within their denomination is shared commitment to this basic cultural structure. As for the EPC, I think the best way to inhabit that confessional/doctrinal structure is to strive for Reformed theology/Westminster confessionalism to become that substructure and conscious framework of our ministry. So for example, when we ask questions like, “What is a healthy church?” the marks of the church are the first things we consider, not church life cycles. When that becomes the norm in the EPC, I think we’ll start to see a clearer picture of what our expression of that will be.

A couple of miscellaneous responses:

– I agree with your observation, Joey, about more recent graduates from certain seminaries – and I appreciate that you are committed to the solution of training these future pastors. Thank you.

– Re: the flow of polity in the EPC – I think it is a historically honest thing to say that the EPC embodies a more cultural northern Presbyterian tradition that tends to deemphasize the grassroots Presbyterian of our southern tradition. This is not a recent shift but inculcated from our inception. Still, your prescription is accurate; but the point I have been repeatedly making over the last several years especially is that ‘our polity only works if we work our polity.’ If Sessions and Presbyteries are not sending overtures then we rely on something else to set our agendas. If not, our present culture guided by our current rules probably means – less floor debates at regional or national courts – and more getting to work within the system (as both of you embody; regional and national committees, etc). Your point might be, that our committee-dominated work forming the direction of the church is the problem, but the way to realize EPC that could be, is by working within the EPC that is. Again, I am thankful that you and many others are doing that. Which is why these conversations are so important.

Cameron and Zach – thank you both.

Cameron – I’m particularly grateful for your thoughts on the marks of the church. Yes – the marks of the Church, the “notes” of the Church (unity, holiness, catholicity, etc.) – these are categories that bring with them the kinds of theological heft that anchor the church through the inevitable storms. It’d be interesting to think about how we can fill this out even more – within local sessions, presbyteries – to create a framework for ministry that is accessible to REs and TEs alike.

Zach – that’s a very perceptive comment about which strand of Presbyterianism the EPC embodies. I’d love to hear more about that. You’ve inspired me to dust off some of my old Presby history books..

This is my first visit to your website, Cameron, and I’m grateful for and in agreement with these proposals. Moving toward decentralized polity is, imo, one of the most important steps we can take. Re catechesis of children, I hope it’s a point of serious conversation at GA this summer!

Cameron, Like David – first time here! And since Joey pointed me here, that makes a trifecta of friends in the comments. I’m really grateful for this – thoughtful, stimulating, and provocative at times. You gave me much to think about. Without your statistical analysis I wouldn’t have stated the problem so starkly, and I don’t have near the acquaintance/assessment of PCA that you have. Like you, I’ve been strongly influenced by Keller’s 2022 year-long plea over those four articles. I hosted a series of discussions on those in our Presbytery (southeast) and I just eagerly pinned your white paper to read. Thank you!

I need to dwell on the polity argument you make: my first draft is I’m not sure I agree, but a patient re-read is in order. But I can offer two things and a suggestion.

1) as Zach notes – my anecdotal evidence is that our presbytery in particular is dismal at any kind of deliberation. That’s a charitable conclusion. I also wish it were more theologically robust.

2) My own story highlights the twin challenges of theology and polity. I grew up in conservative PC(USA) churches, where the theological edge at the popular level was more evangelical than reformed. I do believe deep reformed emphases drove those evangelical convictions, but … in the latter 90s (when I began ministry after college) it was broadly evangelical convictions on scripture/cross/salvation/discipleship that drove the renewals I knew of. I went to Fuller (I wanted a large, bigger-tent theology to learn from and didn’t know where I fit) and there became more Reformed thanks to a magisterially-reformation-influenced systematics teacher. I’ve been doing remedial work since and have grown since 2010 in grasping reformed distinctives, confessional resources, and their ministry implications… but almost nowhere is the EPC in any way encouraging that for me. As you might have guessed, I was at a PC(USA) church that left in 2007 with the first New Wineskins wave and I participated in EPC presbytery in lots of the church receiving after that. As you wrote just below your chart: “the massive influx of PCUSA congregations into the EPC in 2005-2014 masked that the underlying culture and demographics for many of those churches were not primed for long-term health.” I would agree and say that we might be less impressed in hindsight with with the confessional/theological depth or deliberative patience/skill of of many of those, particularly since early 2010s.

A suggestion – which you note – is the huge difference church planting and RUF are making for the PCA. Church planting has some demonstratively statistical impact – I don’t how how you could quantify RUF’s impact. But I’ll say this: I’ve lived and ministered in the southeast for 20+ years, and when our students have gone off to college they have been more likely to gravitate to RUF than any other campus ministry. When they stay in those cities or move, they are likely to go to PCA churches. On balance there are 3-4x PCA to EPC churches (so that makes a difference), but the southern “EPC to RUF to PCA” pipeline has to be a real thing. And when the other major Presbyterian/evangelical student ministry movement imploded in 2010-2015 (PFR/YCM), RYM (with deep confessional/PCA/RUF connections) further became the both the event (for students/churches) and training (leaders/staff) space that pitched in and still gains ground. Along with the RUF and planting that took off in 90s, I want to almost exclusively attribute that 25-49 year old demographic gain to downstream effects of those twin channels… and wonder if there are not a whole lot of formerly EPC students in there. (Same thing my apply in the seminary to ordination route, which is a clear problem for us).

PS David – I would *love* to sit and your feet as you taught on a program for catechizing kids or shared from your experience. The constant challenge I hear is a “yes, but how? Show me effective means…” I’ll seek you out and make that happen at GA!

Church planting is an interesting aspect of the PCA’s growth. Its success, along with RUF, (vis-a-vis other North American church planting and campus ministry efforts) seems to require my first two points above. However, I’m not sure how much church planting is the answer versus investing in churches in places of population. Stefan Paas’ work Church Planting in the Secular West has been invaluable, and has informed some of the PCA’s adjustments over the past decade. I’m also not sure how replicable the PCA’s church planting work is on this side of COVID and the change in how younger generations approach entrepreneurialism. Regardless, cultivating a network of friendly churches within a presbytery is the first step to sustainable church planting, which is what the PCA has done (see: Chris Vogel and the PCA’s work in Wisconsin) and is aggressively pursuing still.

Cameron,

Strong analysis and lots of food for thought. I have been consulting with PCA churches for two years now, and there is a noticeable difference in PCA churches, and in a positive way.

Help me, however, with this. Your statistical observations come from hard data. Yet you jump to doctrinal rigor as the reason for the growth in the PCA without any supporting evidence.

My observation is that the PCA’s heavy, multi-decade investment in church planting has been the reason for their growth (and I’m glad we are doing the same! It was a big emphasis of mine during my term as moderator).

What proof do you have connecting doctrinal rigor to growth?

Case

Hey Case,

Re: church planting, see my comment above. Having been involved in church planting networks in both the PCA and EPC, I can tell you that “effort” is an insufficient explanation for their church planting success and denominational growth. Plenty of denominations have pushed church planting (e.g. the SBC) for decades and have still shrunk.

On the question of cause and effect, I’m making inductive assessments of the PCA. What are significant differences, culturally and programmatically, between the PCA and the EPC that could explain our decline and their growth? What of those differences could explain the PCA’s growth when the majority of other denominations are shrinking? The PCA’s robust confessionalism is a difference; in what ways could that difference in confessional posture explain their growth? I don’t think having robust doctrinal expectations for pastors and ministry is by itself a sufficient criteria for growth (see: the LCMS, CRC), but it is necessary for a confessional denomination. I don’t think decentralized polity, catechizing children, or campus ministries are currently effective for *denominational* growth apart from robust doctrine; my evidence would be literally every other denomination.

Really, what the robust doctrine of the PCA means is that they and their congregants are rooted. Their values and framework are solid and extensive enough to adapt and compensate for cultural change. Unlike the CRC or Lutherans, their rootedness doesn’t have an ethnic or as strictly a regional dimension, and unlike the ACNA (the dust is still settling there, so their trajectory remains to be seen) the PCA’s polity allows for greater adaptation. Perhaps I’m wrong about why the PCA is growing; deductively, I’m taking the premise of Dean Kelley’s 1972 classic Why Conservative Churches Are Growing: A Study in Sociology of Religion and updating the categories from shrinking liberals and growing conservatives of the 20th century to the shrinking “everybody else” and the growing confessional PCA of today. An actual sociologist could look at the data and make some more definitive pronouncements.

[…] Read More […]

Great article! But I am surprised there is no mention of the differences between the EPC and PCA regarding the role of women, particularly with how pervasive gender confusion has become in the US in the past 5 years. Is this a significant factor in light of the differences in the doctrinal standards between the denominations? Would love your thoughts. Thank you.

Hi Matt,

This isn’t a difference in our formal doctrinal standards (the Westminster Confession and Catechisms) but is a difference in our practices. The PCA and EPC are otherwise on the same page about human sexuality (marriage, divorce, the gender-binary, etc). It is unclear to me what difference women’s ordination has made on overall denominational growth one way or the other.

Hello Cameron,

I am a member of a church that is in the process of dismissal from the PCUSA and reception into the PCA. One reason we chose the PCA over the EPC was the ordination of women issue. I also was surprised this issue was not a part of your very informative article. Of course, It wasn’t the only reason; doctrinal rootedness as you described ranked supreme. Maybe an unwillingness to compromise on this so called non essential is more important to growth in the PCA than you think.

I am a ruling elder emeritus in a PCA congregation. During the upheavals in the PCUSA and during covid, we came across individuals and even whole churches that were interested in the PCA.

Frankly, the elephant in the room was female elders and pastors. That proved to be the unbridgeable gap in their moving to the PCA. So if you’re going to talk about confessional and Biblical rigor, you need to refer to LC 158, footnote W, which refers to 1 Tim. 3:2. Also Titus 1:6, which repeats the 1 Tim. 3:2 qualification for an elder to be the “husband of one wife.”

I would think that the EPC, being open to have charismatic and third Wave congregations would be growing faster than the PCA.

Even more so now that there is a growing trend of new charismatic Reformed churches All around the USA SO maybe tbe EPC has not been smart promoting itself among them

[…] Read More […]

[…] Read More […]

I’ve pastored in the PCA both in a northern and now in a southern state. Both times, I’ve made friends in the local EPC church finding them orthodox, and both times, I’ve had numerous folks tell me they won’t even consider the EPC church in town for one reason – egalitarianism. I’m surprised this did not factor in your take at all. It’s the gigantic elephant in the room.

Great thoughts, Cameron. I think you’re right about doctrinal rigor being paramount. People can get the bare essentials of Christianity in many places; there are fewer and fewer churches where they can hear “the whole counsel of God” (Acts 20:27).

I’m an elder at an OPC church in a semi-rural college town where there’s an EPC that used to be PCUSA. We honestly don’t interact very much. I think your observations are borne out here — we have about forty college students every Sunday, and I don’t think the EPC has many, if any at all. To be fair, though, there isn’t a PCA within an hour of us; if a Keller-type PCA were planted here, I suspect some of our students would go there (along with a lot who are currently attending Reformed-ish Baptist churches). The more confessionally minded ones would probably stick with us. This is maybe too broad of a generalization, but we think of the OPC (and a fairly sizable chunk of the PCA) as being consciously Reformed in doctrine, polity, and liturgy; the Keller wing is really only concerned with being Reformed in doctrine.

Also, I regret piling on here, but other commenters are right — egalitarian doctrine and practice has to be considered as part of the doctrinal rigor you call for. Doctrinal rigor first and foremost means taking Scripture seriously (teaching “the whole counsel of God”), and when people start doing that, most of them are going to come to the conclusion that it’s pretty plain that Scripture calls for different roles in the church for men and women. I guess I’m not optimistic that you could raise up a “TR” wing of the EPC without seeing a lot of those people leave for the PCA, OPC, etc.

Thank you for your thoughtful article, Cameron. Two responses, one regarding the Coalition for Christian Outreach (CCO) and one, a reflection on the nexus of EPC polity.

You captured well the spirit of the CCO, which was founded in western Pennsylvania as a coalition between various parts of the evangelical movement, and is still, broadly evangelical in spirit.

The CCO–particularly the Jubilee Conference–has a neo-Calvinist core, best captured by Abraham Kuyper’s “there is not one inch in all of creation about which Jesus Christ does not say–mine!” Kuyper’s Colossians 1 Christology, while not coded in Dutch Reformed language, underpins the CCO’s work with students. The CCO’s first core value is, “all things belong to God.”

The Jubilee Conference is built on a four pillar Biblical platform (Creation, Fall, Redemption, Restoration) and exposes students to the Lordship of Christ over every part of life in a way unique among college conferences. The Conference breakouts are organized by vocational/academic disciplines.

When I think “broadly evangelical” I think Passion. I’ll leave the question of church/CCO partnerships to others who are more current. I’m retired. BTW, the CCO’s Statement of Faith was authored by R.C. Sproul.

I’ve a question regarding EPC polity and our minimalist approach. Have we ever pushed into the “in essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty, in all things charity” calling? What, instead of a low bar for entry, we treated it as a holy aspiration around which we build our institutional life and practices?

My experience with the EPC’s framework at the congregational level reminds me of Chesterton’s quote, “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult; and left untried.”

Keep thinking deep thoughts, y’all!

Hi Dan,

Thanks for the insight on CCO and its neo-Calvinist bent; I was unaware of Sproul’s involvement in its doctrinal statement. Your question about the EPC’s motto is one I’ve been chewing on for years. I’ll keep thinking and posting about it.

Cameron,

Thanks for all the time and effort you put into this article/essay/report. While you’re obviously hoping to see more than conversation come from this, I certainly think you’ve offered something that needs to be discussed, if not given serious address and consideration.

I think your point toward smaller presbyteries is of particular importance. Our connectionalism suffers when distance and the expenses that come with that either preclude or are an excuse for a less than robust attendance, and therefore, participation in presbytery meetings.

I appreciate, too, your honest assertion concerning the investment of time many, if not all, your recommendations require.

At the heart of our denominational struggles is, at least in (large?) part the transfer growth of hundreds of traditional, but doctrinally deficient and barely Reformed congregations whose departure from the PC(USA) was as much as about wishful thinking (that joining the EPC would be a magic-bullet fix for their stagnation) as it was about their rejection of their former denominations perpetual slide into idolatry and paganism. I would imagine (and perhaps hope?) that much of our denominational decline over the last decade, aside from the direct and indirect effects of COVID, is that some of those local church transfers went the way of all flesh, and did so either because churches, like their members do in fact have a life-cycle, or because they were unwilling to embrace the necessary revitalization and revisions necessary. I can honestly say I have seen this and experienced this in my own congregation, as their first (but hopefully not last) EPC pastor. Having preached from, as you put it, a more Reformed and Westminsterian position, expositionally from the whole counsel of God, catechized our students (and our adults), and sought to communicate both the Great Commandments and the Great Commission, I can speak to the reality of people’s resistance to becoming/being a Reformed, and I hope therefore, biblical church. Old habits die hard; so too culture (with both a big C and little c).

My estimation and my guess is that there will be a sizable, and therefore painful, number of those transfer congregations that will continue to close because they want to eat their cultural cake and have the supposed EPC blessings to boot. This speaks to another area that is in great, and I dare say, immediate need is a more rigorous method for interviewing and determining whether such congregations, particularly from the PC(USA) and the like, should truly be admitted and welcomed into the EPC. To wit, what will their congregational DNA do to their admitting presbytery? While such a question is speculative, my experience is that such churches pose a greater challenge for pastors who are committed to a biblical, Reformed vision, as well as lack the desire and willingness to be all in on growing the kingdom of God.

While your report has shown an ugly underbelly of sorts, I am, overall, very thankful for the EPC, it essentials/unessentials tension, and the leadership we’ve had from General Assembly. That’s not to say I disagree with you at all. Your suggestions are worth the time and energy for thoughtful debate so that we might well see a turn around. So, again, thank you for this great effort you’ve shared with us. Hopefully see you at presbytery. God’s blessings on you, your family, and your congregation.

Many commentators have asked about the issue of women’s ordination and the EPC’s growth, which I address in this post: https://cameronshaffer.com/2024/04/02/the-epcs-confession-of-faith-and-womens-ordination/

Cameron, thank you, thank you.

One more factor in the EPC’s crisis is that we must become more theologically rigorous in our pastoral training and examination process (as you discuss), at the very time that we are facing a massive wave of retiring Boomer pastors, and seminaries struggling to recruit students into their Master of Divinity programs. A pastoral shortage is upon us. I believe that the EPC is not alone regarding this challenge.

The temptation, of course, is to lower ordination standards to increase “pastoral output,” out of sheer desperation.

Hello Cameron,

I am a member of a church that is in the process of dismissal from the PCUSA and reception into the PCA. One reason we chose the PCA over the EPC was the ordination of women issue. I also was surprised this issue was not a part of your very informative article. Of course, It wasn’t the only reason; doctrinal rootedness as you described ranked supreme. Maybe an unwillingness to compromise on this so called non essential is more important to growth in the PCA than you think.

Sorry for the re post. I did not see your April4 response.

Hi Pastor Cameron,

A couple of admittedly disagreeing questions regarding your analysis of the numbers:

1. Your article includes nothing on incredible influence that the internet celebrity status that Tim Keller had on PCA churches and plants in the 2000s-2010s. The EPC has had no attractive nationally renowned pastors at this level. Anecdotally, from being the PCA during those years I can cite dozens of pastors and Believers who joined PCA for the soul reason that it was Keller’s denomination. What do you make of this factor?

2. In the post-Keller PCA, which began before his passing, there has been a marked shift towards political homogeneity towards the Right. The PCA is now considered a bastion of Conservative perspectives and soundly “anti-woke”. Much of the Trump-Era “growth” that I have witnessed has come from churches and individuals seeking this branding. This would seem to explain the dip and recovery around the pandemic. The EPC, on the other hand, has tried to stay largely politically neutral creating a lack of brand clarity. Don’t you see this as a major factor?

3. By far and away the most troubling underlying premise here is that growth in denomination equals Kingdom growth. The PCA thrives on “sheep-stealing” or transfer growth. There are no numbers here indicating conversions to Christ. Furthermore, your list of reasons for PCA growth include zero ideas that are relevant to unchurched people. There are no metrics about reproductive discipleship models in the PCA. Certainly, the PCA is winning the war of “reshuffling the chairs on the Titanic”, but why should we really care about who’s institution wins this fight?

Thanks for putting your work into this piece.

Love and respect.

Josh Speyers

Hey Josh,

Good to hear from you. In reverse, this post was about denominational growth, which is a good thing. I’m not able to discuss everything that touches that topic in a single post, as is evident from the multiple follow-up posts I’ve since put out. That being said, I have consistently in my public writings (search the blog) and ministry rejected equating numerical growth with spiritual growth, and in this post I made multiple statements to that effect. My very first caveat in the introduction was an acknowledgement that denominational growth and kingdom growth are not always the same thing and kingdom is more important. I also provided data on the adult conversions and baptisms that happened in the PCA.

I’m not sure what to make of the Keller factor. His influence was large, but perhaps overstated for the PCA’s growth. The PCA’s rate of growth has been consistent since the 1980s, before Keller’s influence, and has continued since his retirement. Same with the conservative bent of the PCA. Joey Pipa and Morton Smith were founding fathers in the PCA. The PCA’s debates over creation, the new perspective, intinction, etc., all had the same conservative dimensions as their current debates. It doesn’t seem to me that the PCA as a whole is all that different culturally from my time in it. Perhaps the PCA is either going to shrink post-Keller or consolidate as a (more) politically conservative denomination. I doubt it though, but time will tell.

Fascinating article and full of food for thought. I’ve been doing RUF for almost 30 years (and in the PCA for maybe 38 after being raised liberal Episcopal.) I’m also the founder of Indelible Grace. The PCA feels different then when I began, more rigid and culturally conservative, and I am increasingly losing students to more egalitarian churches, so it is very interesting to read this outsider’s take. And fwiw, I don’t think Indelible Grace is as ubiquitous in RUF groups as it used to be – some of that is intentional.

This a thoughtful post with a gracious tone, but I believe the conclusions are a bit misleading.

First, let me be clear…I love the PCA! I served in the PCA as a missionary with MTW. Like Twit, I was an RUF campus minister. Then, I planted a church with MNA. I’ve seen the PCA from many angles over the past 25 years. Last year, I transferred by ordination to the EPC, where I now serve as a Regional Director for Church Planting. BTW, my doctrinal commits haven’t changed a bit. I’m proud to be a 12 point Calvinist and a Reformed Systematician. I’m all in!

You make lots of insightful points that I readily affirm. However, I take issue with premise behind the title of your article and believe you’re overly simplistic in your description of the PCA’s Reformed Confessionalism, and therefore, misguided when pointing to the PCA’s Reformed Confessionalism as a primary cause of its relative growth/health.

Just a few reflections in response…I believe that the primary lesson for the EPC to learn from the PCA is that doctrinal alignment does not necessarily translate to missional alignment. You see, there are at least two camps of people in the PCA, who would wholeheartedly champion Reformed Confessional commitments. Nevertheless, these two camps are missionally, epistemologically, and culturally radically divergent. They are largely, doctrinally in lockstep but when it comes to ethos and posture, they fight…a lot…a lot a lot…or at least one group picks a fight quite often with the other. Why? Because one camp assumes that Reformed Confessional presupposes strict and absolute subscription, where all Confessional articles and all doctrinal truths seem to hold equal weight. In turn, every truth is worth fighting for, because any concession threatens the system of doctrine as a whole. This group tends take a defensive posture both to “the world” but also to those who are deemed “less authentically Reformed.” The primary ministry aim of this group appears to be guarding the truth. Alternatively, the second Reformed Confessional group, significantly influenced by Keller, focuses on the impact of grace on an individual’s spiritual formation and the church’s missional advancement. This group is determined to contextualize their Confessionalism, which the first group assumes invites a fatal doctrinal compromise. The second group measures its Reformed Confessional faithfulness by personal devotion and evangelistic influence. This group tends to embrace redemptive risk-taking in contrast to the protectionism of the first group.

In your article, you fail to distinguish the types of Reformed Confessionalist in the PCA. They agree on orthodoxy but wildly disagree when it comes to orthopraxy and culture. I believe the missional Reformed Confessionalist have served as a huge catalyst for the growth and health of the PCA. But as Twit mentioned, these “big tent” Reformed Confessionalist are being increasingly marginalized and exhausted by the Reformed Confessional fundamentalists. What’s the future of the PCA? I pray it’s amazing! But doctrinal alignment is not enough…and, I don’t think, primary.

If I could suggest a rewrite to your article, I would entitle it “What the EPC needs to learn from the EPC!” There’s a reason the EPC is often referred to as “The Enjoyable Presbyterian Church,” and it’s not simply their refusal to fight and let everything go. The EPC’s original conviction that our system of doctrine, rightly understood, includes essentials and non-essentials, offers a realistic and robust opportunity to hold the tension of missional unity and diversity. The EPC doesn’t need to mimic an idealized version of the PCA. The EPC needs to live more fully into what it says it is, a gracious Reformed Confessional denomination that doesn’t view every secondary issues as a threat to primary doctrines. I honestly believe that the EPC is, at least in its founding principles, what the missionally-minded Reformed Confessionalists wish the PCA was.

Again, thank you for inviting this discussion. It’s worth having. May God be gracious enough to use both denominations in incredible ways for many years to come!

Funny to stumble on an article and find half my friends in the comments already – what up Joey, Hunter, Kevin and Chase!

As a PCA pastor, I feel like I could have written a “What the PCA could learn from the EPC” article and include the inverse of most of what you wrote. Less doctrinal rigidity and in-fighting, greater centralized coordination, more flexibility in methodology, etc. I think you are correct in your assessment that RUF and a consistent pursuit of church planting over decades has really helped the PCA. The positive influence of Tim Keller is hard to overestimate. Your article helped keep me from a “grass is always greener” impulse that can plague me (usually right after GA). Overall it served as a reminder that health is usually found in living within tensions and adjusting to context as needed. There is a generative tension to be found in balancing the goods between grassroots mission and centralized pursuits, defense of primary doctrines and flexibility in secondary matters, etc. I love my EPC friends, and hope for the flourishing of that denomination.

As an observation – I think we are witnessing a major realignment of associations within American Christianity. The culture of the PCA feels very up for grabs right now and I’m not at all able to say what we will be in ten years. It would not shock me at all if the denominational landscape within Reformed evangelical groups looked very different in a few years time.

Hello PCAers who have found this. Thanks for your interest in the discussion. A couple of quick comments.

First, I don’t think the PCA is perfect and have criticized it in the past. I do believe that there are a lot of things the PCA could learn from the EPC. I have written lot on this subject, not just this single post.

Second, this post wasn’t a history and analysis of the PCA’s growth (or vulnerabilities), but looking at things that the PCA has successfully done that the EPC could stand to learn from. I’ve done similar posts on other groups and denominations, not just the PCA.

Third, I suspect that the turmoil in the PCA has been overstated in terms of long term health. I could be wrong (time will tell), but the PCA has grown since the National Partnership/GRN conflicts, Vanguard presbytery forming, and the Revoice debate. The consensus the PCA landed on regarding Side B issues was broad. Maybe there is more to come, but I think the PCA will be larger and healthier in 10 years from now.

Fourth, Keller was a huge influence in the PCA. The EPC (and the PCA!) can’t reproduce him, so that’s not really something we can learn from the PCA. However, on the one hand Keller’s draw has been overestimated. He only broke out into a “superstar” profile around 2005-2006. The PCA’s growth prior to that can’t be singularly attributed to him and I’m skeptical that his association with the PCA in retirement contributed to the PCA’s growth over the last five years.

On the other hand, I think Keller’s doctrinal rigor is being underestimated here. His ethos wasn’t doctrinaire, but he was confessionally Reformed. His emphasis in ministry and leadership might not have foregrounded that, but it consciously was the substrata of his pastoral ministry. He said as much on many occasions. I think the PCAers in this thread are simply unaware of the vast ignorance and disregard of Reformed theology in the EPC. There is no “Kellerite” wing in either the PCA or EPC without robust confessionalism, which is not the same as strict subscriptionism and making all confessional points equal.