Confession and Culture in the EPC

Every time I make some variation of the case that the EPC should lean into its Westminsterian, Reformed heritage, I am asked whether in doing so the EPC would lose its ethos. This reaction emerged to my “What the EPC Can Learn from the PCA” post. Usually the PCA’s more rigorous (rigid?) confessionalism is inferred to be part of a contentious dynamic, and that embracing a more confessional posture on the EPC’s part would sacrifice our ethos. In these cases, higher doctrinal standards, greater confessional rigor, and intentionally cultivating a Reformed identity are all assumed to be at odds with the culture of the EPC.

One of the biggest challenges facing the EPC is imagination. We struggle to imagine what a confessionally-grounded approach to ministry and polity would look like. When it comes to the PCA vs. EPC, we struggle to imagine how we could be confessionally rigorous without losing our relaxed ethos. This is a common sentiment, and it’s actually quite revealing — confessionalism is confessing what God teaches in scripture. The Westminster Confessions and Catechisms may get that wrong, but as a church the EPC confesses that we sincerely believe that they get the teachings and system of scripture right. The fear of some is that if we become more confessional then we will lose our ethos. If we have to choose between being faithful to our confession of faith and our “ethos” we should choose faithfulness every time…

What the EPC Can Learn from the PCA

There is much my own Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC) can learn from the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). Although the EPC and PCA hold to the same doctrinal standards, the EPC is shrinking while the PCA is growing. The EPC can learn a lot from our larger partner about how to remain faithfully confessional and missionally relevant in post-Christian America.

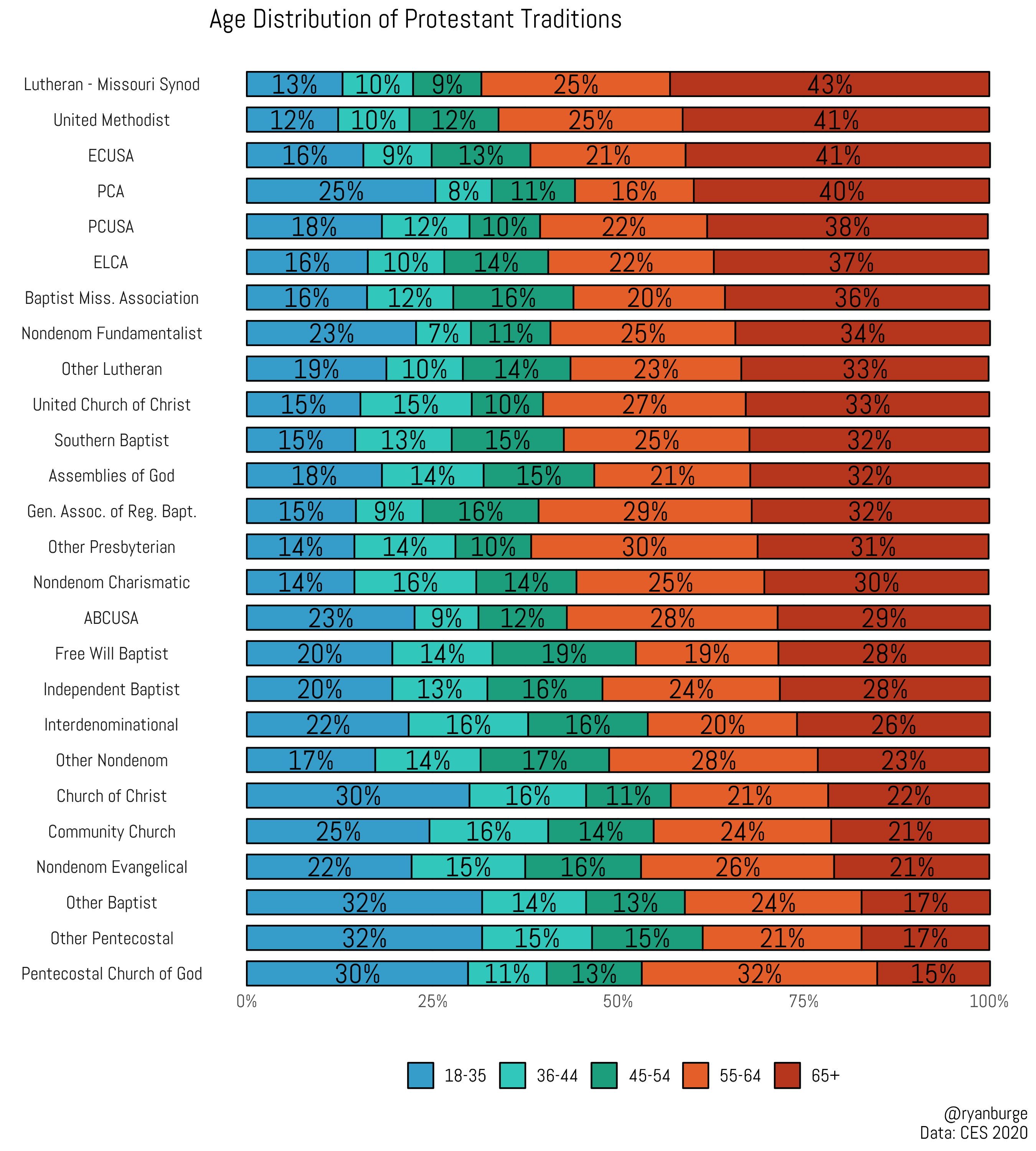

Broadly speaking, the PCA is the only non-Pentecostal denomination still growing in the United States. That should cause every leader in the EPC to pay attention: the only non-Pentecostal denomination still growing in America is a confessionally Reformed, doctrinally rigorous church, and it’s not us.

So, here are the usually caveats at the outset. First, while the EPC should desire for its congregations to grow and to become a bigger denomination, our first goal should be to see Christ’s kingdom grow. Second, numerous individual EPC congregations are growing and healthy and some PCA congregations are shrinking and unhealthy. But on the whole, the EPC is shrinking while the PCA is growing, and I am focused on the general contours of both churches. Third, applying principles of denominational growth to individual congregations is immensely difficult. That requires a culture shift and buy-in. Fourth, most of what makes the PCA successful required steps it took 30-40 years ago. The EPC could try and replicate the PCA’s current practices, but without a similar foundation those practices will flounder. At the same time, the EPC cannot simply duplicate what the PCA was doing from 1984-1994 in 2024; the world is different, and so the application of this foundation will by necessity look different…

A Summary of Actions Taken by the 43rd General Assembly of the EPC

This week my denomination, the Evangelical Presbyterian Church, held its 43rd stated General Assembly in Denver, Colorado. This is the annual meeting and council (synod) of my church, and every pastor has a right to attend and every congregation may send elder representatives. This was the first GA I did not attend since I was ordained in the EPC, though my congregation did send representatives. This GA was also unusual in that it was officially treated as a conference (“Gospel Priorities Summit”) wherein the training and plenary talks were intermingled with business, were thematically connected to the EPC’s strategic (now “gospel”) priorities, and had a 3-day runtime instead of four. Below is a summary of the official actions taken by the assembly…

Women’s Ordination in the EPC: Learning from the CRC

The EPC occupies a rare place in Reformed evangelicalism. We allow for the ordination of women, but we do not require our officers to affirm women’s ordination, nor require churches to ordain women, and permit presbyteries to have male-only teaching elders. This subject is one of the few the EPC has formally identified as a “non essential” where there is room to disagree.

The EPC is not unique in our approach. The Christian Reformed Church of North America (CRC), which is an official ecumenical partner of the EPC, has a very similar position. Unlike the EPC, which was founded in 1981 and has had this position on women’s ordination since then, the CRC is a church with its roots in the Neo Calvinist movement in the mid-19th century and only began allowing women’s ordination 25 years ago. That led to schism and the formation of the URCNA. For the EPC, the issue is one we have settled from the outset: freedom for all views. For the CRC, the ordination of women is seen as part of a larger trajectory, for good or for ill.

How’s that going? Following the CRC’s recent adoption of their human sexuality report, a group has emerged calling for the church to adopt a third way, allowing room to agree to disagree on LGBT issues. They cite the CRC’s success with women’s ordination as an example of this possibility. CRC Pastor Eric Van Dyken assessed the state of things recently, and this excerpt is worth including at length…

The EPC and the World Communion of Reformed Churches

Below is a report I wrote in 2021 assessing my denomination, the Evangelical Presbyterian Church, remaining a member of the global ecumenical body the World Communion of Reformed Churches. I wrote this as a member of the EPC’s committee on theology to assist our committee on Fraternal Relations to think through that membership in light of the EPC’s revised endorsement policy. At the 2022 General Assembly, the committee on Fraternal Relations was instructed (at their request) to formally evaluate the EPC’s membership in the WCRC and to bring a recommendation for action to the 2023 GA. While the official recommendation has not yet been made public, the expectation is that it will encourage us to end our membership in the WCRC. The WCRC is more aligned with mainline and liberal churches in North America and Europe (such as the PCUSA) than evangelical churches, and the North American and European contingents dominate the ethos and meaningful leadership of the WCRC. This is the real reason the EPC would consider leaving: the WCRC is not a good fit for missional partnership.

I believe the EPC should remain a member of the WCRC, though only if we’re willing to actually engage it. There is a significant shift happening on a global level in the church (e.g. the changes in the Anglican Communion and among the Methodists) where the leadership is moving towards evangelical churches in the majority world. I think the EPC could stand to benefit from being part of global council of churches committed to the Reformed tradition, especially as things are changing. So below is a lightly edited version of the report I submitted in July 2021.

Historical Considerations

In 2011 the EPC instructed the Fraternal Relations Committee to evaluate all of our fraternal partnerships. This included the WCRC. At the time, part of the concern over the WCRC was our sharing a membership with the PC(USA), which had just revised its ordination vows to accommodate homosexual relationships. The FRC’s report, adopted by the GA in 2012, said this about the WCRC…