A Review of “Three Circles”

Turning Everyday Conversations into Gospel Conversations (Three Circles) by Jimmy Scroggins and Steve Wright has become a favorite evangelistic tool in Baptist circles. The North American Mission Board (the domestic mission arm of the Southern Baptist Convention) has adopted it and even created a companion website and app.

Scroggins and Wright are motivated to share the gospel with as many people as possible and to equip the people of the church to this end. A laudable motivation, to be sure. They are driven by a desire to see a multiplying church, especially in their unchurched South Florida context.

Now, a word needs to be said about whether South Florida (the authors are in West Palm Beach) is unchurched. They assert that 96% of the 1.4 million people in South Florida are unreached and that West Palm Beach is an unreached city (pg. 17), an assertion that is repeated regularly throughout the book. This, to put it bluntly, is inaccurate. The 96% unreached number comes from NAMB, which provides no data to back up their claim. They cite a 2015 Barna study which says that West Palm Beach is the city with the highest percentage of “never-churched” people in the United States (17%), but that means 83% of West Palm Beach has been churched at one time. That very same Barna report states that West Palm Beach is currently 52% churched, 48% unchurched, the 11th least-churched city in the country, but hardly unchurched or unreached. The Association of Religious Data states that in 2010 (most recent year for their data) Palm Beach County had a rate of 36.6% regular attending Christian adherents, with 10.9% of the population regularly attending an Evangelical Protestant church. No matter how you massage the numbers, South Florida is not unreached. That does not mean that sharing the gospel should be a lower priority, but that does mean Scroggins and Wright made me skeptical of their work. Misleading the reader on one point, intentionally or through unintentional sloppiness, means you’re untrustworthy on the others. When so much of the book’s argument is validated by the alleged effectiveness of the tool in converting the unreached, while it turns out the number of unreached is vastly overestimated, it calls into question the effectiveness of the tool and validity of the book’s argument.

The pathos of the book will be familiar to anyone acquainted with the SBC world, especially the work of David Platt, who makes an appearance. There is a sense of desperation to reach the lost that subordinates every other concern to this single cause. Christian life and piety become all about this single, overarching objective: getting the lost converted. Sharing the gospel and seeing the lost saved are good, but this culture produces an anxious restlessness and guilt, and obscures the God-centered, doxological mission of the church. Michael Horton’s Ordinary: Sustainable Faith in a Radical, Restless World (2014) and John Murray’s “The Church and Mission” in Volume 1 of his Collected Writings provide a far better and Reformed vision of the Christian life and mission. Three Circles is what you would expect from a Baptist, rather than Reformed, understanding of the Christian life.

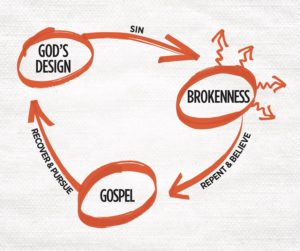

The appeal of Three Circles is the simple tool provided so that anyone can have a gospel conversation. You are to look for instances when a conversation exposes the felt brokenness of other people and then share the gospel. Drawing three circles (God’s design, our fall into brokenness, the gospel of Jesus offering healing leading back to restoration of God’s design) is simple, clear, and direct.

The best part of the book is the encouragement to every Christian to be willing to share their faith. Calling people to practice how they share the gospel and reminding them to invite people to respond to the gospel are good things, and I appreciated Scroggins and Wright emphasizing the practicalities of gospel conversations. There is something to learn there. However, I do not believe the three circles tool is salvageable for two overarching reasons.

Denigration of the Visible Church

The Bible uses many metaphors for the people of God, such as the body of Christ, the family of God, and sheep under a shepherd. Scroggins and Wright seem to prefer military recruitment: you are converted so that you may be deployed. This is Christianity as a multi-level-marketing scheme.

People are instructed to rehearse the conversations in which they’ll share the gospel. Constantly. On your own. With your kids. In your small group. In children’s Sunday School (page 46). The idea is that we are comfortable talking about sports or media, and practice things like our golf swing, so we should practice how to transition conversations to the gospel (page 38, 46, 63). This misses the heart of how we should talk about Jesus. People talk about sports and media because they delight in those things. Those conversations are natural, not scripted. Talking about the gospel requires preparation, but preparation through discipleship.

Normal people don’t rehearse conversations in advance. They have conversations. Sales people and telemarketers rehearse conversational scripts in advance, and the non-Christian will be well aware of this. The strange move that Scroggins and Wright make is to insist that evangelists shouldn’t worry about the specific concerns that non-Christians might have with the faith (page 61-62, 65). The tool (the script) should do all the work, and if it is not effective (a “red light”; page 65), move on. They don’t seem to consider that the secular turn in the United States may have been influenced by decades of evangelicals ignoring the real, skeptical hesitations of the world in favor of simplistic scripts that see people as marks.

Instant redeploying of converts, an essential aspect of Scroggins and Wright’s missional strategy (page 18, 23, 24, Chapter 7), sends unequipped, unprepared, and undiscipled people into the field. God can use anyone, but in his word God reveals that the church should use those who are equipped and prepared. The Bible does use martial imagery, but to stress endurance and preparation, not sending the unequipped to the front lines. Scroggins and Wright rightly emphasize that Matthew 28:18-20 instructs the church to obey Christ, but miss that this is an instruction to observe all that Christ has commanded, which is not a rapid turnaround process. Being discipled into obeying Christ is not the same thing as being commissioned to rapidly disciple others to obey Christ. Relying on a limited script instead of meaningful conversation driven by an internalization of scripture is a recipe for evangelistic malpractice.

“Not many of you should become teachers, my brothers, for you know that we who teach will be judged with greater strictness.” You would have no idea this verse or similar sentiments are biblical while reading Three Circles. Everyone is a missionary commissioned to teach the message! (page 37). This is premised on the claim that in the United States “come and see” what Christianity is about is no longer a viable evangelistic method (page 17). This conclusion is asserted, not proved. Biblically speaking, the worship and ministry of the church is not incidental to the Christian faith, but is the divinely established vehicle for proclaiming the gospel. It is foolishness to the Greeks and church growth gurus.

With frequent consistency Three Circles denigrates the pastoral office and necessary training to be equipped to handle God’s word. All of the many references to seminary are dismissive. Three Circles instead elevates a conception of the priesthood of all believers that sees every individual Christian as divinely called and commanded to be near-instantly capable and willing to share (i.e. teach) the gospel. The Great Commission is asserted to have been given to every individual Christian (page 10, 11, 18, 24, 31, etc.) despite Matthew 28:18-20 being clearly addressed to the apostles.

To make their case, Scroggins and Wright cite examples of the gospel being shared in Acts and the ministry of reconciliation in 2 Corinthians 5:17-21. In the former, they seem not to notice that literally every example they give is of either the apostles and other church officers evangelizing or a description of the general ministry of the church (page 41). There is no example in Acts of individual, non-ordained Christians sharing the gospel in a mass movement. The closest example of this is Apollos, who needed to be taken aside and instructed since he was not correctly teaching the gospel. Bizarrely, Scroggins and Wright use Apollos as an example of the allegedly-biblical mandate for every Christian to share the gospel on their own (page 71). On 2 Corinthians 5:17-21, Scroggins and Wright assert, again without evidence, that the “we” who has the ministry of reconciliation is every Christian (page 15-16). This requires a serious decontextualization of 2 Corinthians, which is built on Paul vindicating his apostolic ministry (e.g. 3:1-6, 4:1-5, 7-12, 5:11-13, 6:1-13, etc.).

Scroggins and Wright do acknowledge that the three circles is simply a tool to share the gospel of Jesus, but misstep in asserting that the specific tool does not matter (page 31). Rather, the Bible teaches that God divinely instituted the preaching of his word and the administration of his sacraments to show forth the gospel. The tools matter, and the nature of God’s ordinary tools of grace means that individual Christians should enthusiastically share the gospel with the words, “Come and see!”

Missing the Gospel

The gospel as presented in Three Circles is emaciated and truncated: People experience brokenness in life, which is a deviation from God’s design; Jesus then offers us restoration to God’s design, healing of us of our brokenness in this life.

Brokenness is identified as the real problem all people face. Sin is described as the cause of brokenness and the character of broken practices, but not the problem itself (page 30). Sin is relegated to an exclusively volitional position: I experience brokenness because I chose sin, even if I am a sinner from birth. No mitigating factors are considered, though individual repentance is seen as the solution to social brokenness (page 15). If Jesus used the three circles to respond to the disciples’ question “Who sinned? This man or his parents?” his answer would be: This man.

Three Circles does not teach that sin is transgression that needs forgiveness, even though it is sin as a moral condition which truly separates us from God. Scroggins and Wright reduce guilt to a feeling, a part of brokenness that needs to be repaired (page 53). The broken condition of their world is exclusively individual and therapeutic, not cosmic and forensic.

Brokenness is certainly part of the sinful human condition for which we need salvation, but Scroggins and Wright make it the condition. The problem Jesus is sent to solve is our inability to move from brokenness back to God’s design. His death, though substitutionary, is intended to empower us to make that move. Three Circles is an effectively Arminian presentation of the gospel: Jesus in his death does not save us from sin, but equips us to repent, meaning our turning from brokenness back to God’s design, which is what needs to happen to be made right in God’s eyes (page 15, 55, 65). “When we repent and believe in [Jesus], He gives us supernatural power to recover and pursue God’s design” (page 31). Salvation is what we choose in repentance, not something that Jesus has definitively accomplished for us. Ongoing repentance in the Christian life is about us making our choice, now that we have been equipped to do so, to return from brokenness to God’s design (page 30, 50, 55-56). It is our repentance that “forgives everything” (page 56).

The gospel of Three Circles is that the hardness of life reveals your brokenness, to which Jesus is the empowering solution. Repenting and believing in Jesus moves one from the circle of brokenness to the circle of God’s design and not-brokenness. Brokenness is not defined as an objective alienation from God, but a subjective sense of suffering (page 15, 30, 40). It is assumed that everyone feels this brokenness, and the evangelist just needs to find an opening to present the solution. And when the lost don’t feel this brokenness? Well, Three Circles doesn’t even consider this possibility.

What the gospel of the three circles does present is ongoing and present healing of brokenness by returning to God’s design. This is spiritually toxic. Redemptive history moves from creation to fall to redemption to consummation. This fourth stage is conspicuously absent from the three circles, which flattens eschatological hope into the here-and-now (there is a single, passing mention of life forever in God’s presence, page 33). Simply put, Three Circles teaches that the gospel heals brokenness (disease, divorce, disappointment, death, etc., in issues of parenting, marriage, work, money, and cancer, etc., page 15, 45) through personally repenting back into God’s design, now. There is a single caveat that repentance doesn’t “fix everything” (page 56), but this single, unnuanced clause is lost in the overall message that turning to Jesus heals us of our brokenness.

Three Circles acknowledges that people look to all sorts of places, including the church and religion (page 51), to unsuccessfully address their brokenness. But what happens to the convert’s hope in the gospel when they don’t experience restoration from brokenness now? If the gospel is restoring people to God’s design in this life, and they don’t experience that restoration in this life, the gospel has failed to deliver on the evangelist’s promise. This is the health and wealth gospel. The Bible nowhere promises this. Poverty, affliction, indwelling sin, addiction, racism, loneliness can all beset the Christian in this life. Take up your cross and follow me! I die daily! I have been crucified with Christ! The way of the Christian is the way of the cross. Nothing about the gospel suggests that repentance will bring healing to your marriage or restoration to your estranged children, contra the chief example of the three circles tool (page 50-57). To present the gospel as the material solution to marriage brokenness is false advertising, and sets up the convert for more guilt and the church for victim blaming. “Why did her marriage not improve? She must not have repented enough to be back in the circle of God’s design.”

This is what happens whenever Jesus is reduced as a means to an end. Jesus’ role in the gospel of the three circles is to empower people to choose God’s design and receive restoration now. Jesus is not the object to which we are saved, to enjoy forever in union with him, but a bridge to the good life. When the gospel is presented on the foundation of our experiential testimony (page 57) with the promise of a matching experience for the convert, Jesus is not the foundation of the Christian’s hope. True faith is trusting that because of what Jesus has done we can be saved from our guilt and brokenness, and that though we now only see in mirror dimly, Jesus is going to consummate his gracious work of salvation as we behold him face-to-face. The hope of the gospel is that we are not our own, but belong in body and soul, in life and death, to God and to our faithful savior Jesus Christ.

And any message of salvation that fails to have Jesus as its end is not the Christian gospel.