The Essentials Mean What Westminster Says

“The Essentials are set forth in greater detail in the Westminster Confession of Faith.” These are the final words of the Essentials, present since its drafting in 1981. This states clearly what was reaffirmed throughout the EPC’s history: the Essentials (singular!) is a summary of belief, with the WCF as the fuller account. For the Essentials to be set out in greater detail in the WCF implies that there is an agreement between the two documents, with the WCF’s meaning taking priority over and defining the meaning of the Essentials. The point of this quotation is to affirm that no matter how extensive the Essentials is, its full meaning is found in the WCF. In other words, the Essentials is not an expansion of the WCF that could be reasonably understood to contradict the WCF. Otherwise the WCF would be set out in greater detail in the Essentials! The Essentials is a summary, the true meaning of which is in the WCF. The position of the EPC, then, is that the Essentials mean what the WCF says.

This is the key statement in the third part of my 2019 series on confessionalism in the EPC. My argument in this third section hits these points:

- The Essentials is the

essentials of being an evangelical , but its use as an essential distillation of what it means to a Christian, or being orthodox, of distilling the meaning of the Westminster Confession of Faith, or summarizing what EPC officers need to believe, or that it encapsulates the beliefs of the EPC, is common in the church. None of these alternatives are accurate or work.

- Deleting the Essentials takes nothing away from the doctrine of the EPC, while deleting the Westminster Standards would radically alter our character. In that sense, the Essentials contribute nothing to the EPC. However, it is common to hear people say that they are in the EPC because they can hold to the Essentials and do not need tot worry about Westminster. This produces confessional schizophrenia.

- Taking the Essentials at face value shows contradictions with the WCF. Yet, the EPC insists that there is no contradiction. The only tenable conclusion is that the Essentials mean what Westminster says. This again makes the Essentials confessionally meaningless.

- The process for making the Essentials constitutional failed to reckon with the incompatibility between it and the Westminster Standards. The Essentials’ constitutional role is already ambiguous (not part of the Standards or the Book of Order, nor part of the ordination process), but the lack of due diligence on this point makes the legitimacy of the Essentials’ constitutional addition suspect.

Reassessing the EPC’s Modern Language Westminster Standards

In 2019 I started a series on confessionalism and the EPC. My initial post received a lot of pushback and interest. That combination led to some good friendships developing and a hesitation on publishing the rest. Now I’ve decided to get the remaining, written parts of the series out there.

All posts in that series can be found here. The first article focused upon the EPC’s amendments to the Westminster Standards and can be found here, something I’ve written about additionally and more accessibly here.

This is Part II, on the EPC’s modern language versions of the Westminster Confession and Catechisms. In summary, I argue that,

- The EPC never adopted the modern language versions of the Westminster Confession and Catechisms. At different points the EPC has approved them for use or publication, but never adopted as the official doctrinal standard of the church.

- The original language version of the Westminster Confession and Catechisms were the original constitutional standard of the EPC, meaning that they are the default standard, not the modern language. If the modern language versions are to be used as the doctrinal standard of the church they would need to be approved following the constitutional amendment process.

- There are significant differences in content between the original and modern language versions of the Standards. The doctrine of God, the imputation of sin, the nature of justification, the accomplishment and application of Christ’s redemptive work, and the nature of the church and its ordinances are all articulated differently in the modern language version. These are significant areas of theology with significant divergences from the constitutional and original version of the Westminster Standards.

- The modern language versions, whether or not they were formally adopted by the EPC, are functionally the confessional standards of our church. They are promoted, published, and used in ways that the original is not. With the differences between the two versions being significant, without proactive reinterpretation by pastors, the modern language version will mislead congregants. Their use should be ended, and if a modern language version is really desired, then a more conservative and less inventive alternative should be endorsed.

Church Life, Health, and Mission in the EPC’s Presbytery of the East

I’ve drafted a white paper as a proposal to guide a presbyterially strategized, congregationally executed approach to church health. It is tailored to the EPC’s Presbytery of the East, where I am and the congregation I pastor are members. But the principles apply to any connectional denomination. David Brooks recently in The New York Times highlighted Tim Keller’s 8-point plan for Christian renewal in the United States. Jake Meador today drew out some of the implications of this plan for institution building. That is what this paper I drafted is trying to capture: a fresh, rooted, and aggressive approach to concrete institution building oriented by the church as God’s institution for mission.

The paper can be found here. Below is an excerpt of the first section.

Church Life

The church receives its life from Jesus. The church is united to him spiritually and mystically, and receives its life from him. He is the vine, we are the branches. No approach to church health, revitalization (i.e. literally “re-lifeing”), or mission can proceed biblically without this reality foregrounded.

Churches are alive and healthy insofar as they truly united to Christ and practicing the means by which that union is deepened. Any conversation about church life cycles, budgeting practices, change management, congregational outreach, effective small groups, etc. is all tertiary to the redemptive work of God in Christ and the means by which the church receives those benefits.

Assuming this or backgrounding it in conversations about church health and mission only results in unhealthy churches and mission unaligned with God…

Thoughts on Descending Overture 21-D

One of the byproducts of Presbyterianism is that if you find yourself in a minority position on a constitutional amendment you have the distinct unpleasantness of being on the losing side of a vote three times in a single year. But three votes is three votes, not two votes, so though I have already been on the minority side on two votes on Descending Overture 21-D, it is not bad churchmanship to again make the case to decline its ratification. Presbyterian decision making is about process and persuasion, after all…

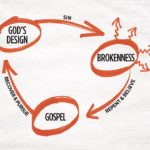

A Review of “Three Circles”

Turning Everyday Conversations into Gospel Conversations (Three Circles) by Jimmy Scroggins and Steve Wright has become a favorite evangelistic tool in Baptist circles. The North American Mission Board (the domestic mission arm of the Southern Baptist Convention) has adopted it and even created a companion website and app.

Scroggins and Wright are motivated to share the gospel with as many people as possible, and to equip the people of the church to this. A laudable motivation, to be sure. Thy are driven by a desire to see a multiplying church, especially in their unchurched South Florida context.

Now, a word needs to be said about whether South Florida (the authors are in West Palm Beach) is unchurched. They assert that 96% of the 1.4 million people in Florida are unreached and that West Palm Beach is an unreached city (pg. 17), something that is repeated regularly throughout the book. This, to put it bluntly, is inaccurate. The 96% unreached number comes from NAMB, which provides no data to back up their claim. Yes, the cited 2015 Barna data says that West Palm Beach is the city with the highest percentage of “never-churched” people in the United States (17%), but that means 83% of West Palm Beach has been churched at one time. That very same Barna report states that West Palm Beach is currently 52% churched, 48% unchurched, the 11th least-churched city in the country, but hardly unchurched or unreached. The Association of Religious Data states that in 2010 (most recent year for their data) Palm Beach County had a rate of 36.6% regular attending Christian adherents, with 10.9% of the population regularly attending an Evangelical Protestant church. No matter how you massage the numbers, South Florida is not unreached. That does not mean that sharing the gospel should be a lower priority, but that does mean Scroggins and Wright made me skeptical of their work. Misleading the reader on one point, intentionally or through unintentional sloppiness, means you’re untrustworthy on the others. When so much of the book’s argument is validated by the alleged effectiveness of the tool in converting the unreached, but it turns out the number of unreached is inaccurate, it calls into question the effectiveness of the tool and validity of the book’s argument…